Earlier in the week, a post came up in my Twitter feed that stopped me in my tracks before sending me down a rabbit hole that I think I may be in for a while. No, it wasn’t a post about indictments or climate change or one side screaming about how they were wronged by the other. It wasn't even about her emails. This was a post about a watch—or at least the possibility of a watch—by a designer named Sebastian Stapelfeldt, who publishes under the name Carl Hauser. It’s a terrific 3D render that looks like something out of one of Syd Mead’s sketchbooks, which is one of the reasons it caught my eye. If that reference doesn't mean anything to you, Syd was an industrial designer and illustrator who is probably best known for his work on Blade Runner and Tron. I think first discovered his work in the late 70s, about the same time that I first saw the work of Frank Frazetta. Both of these guys were huge inspirations, though Syd's influence didn't really show up in my work until the mid-90s.

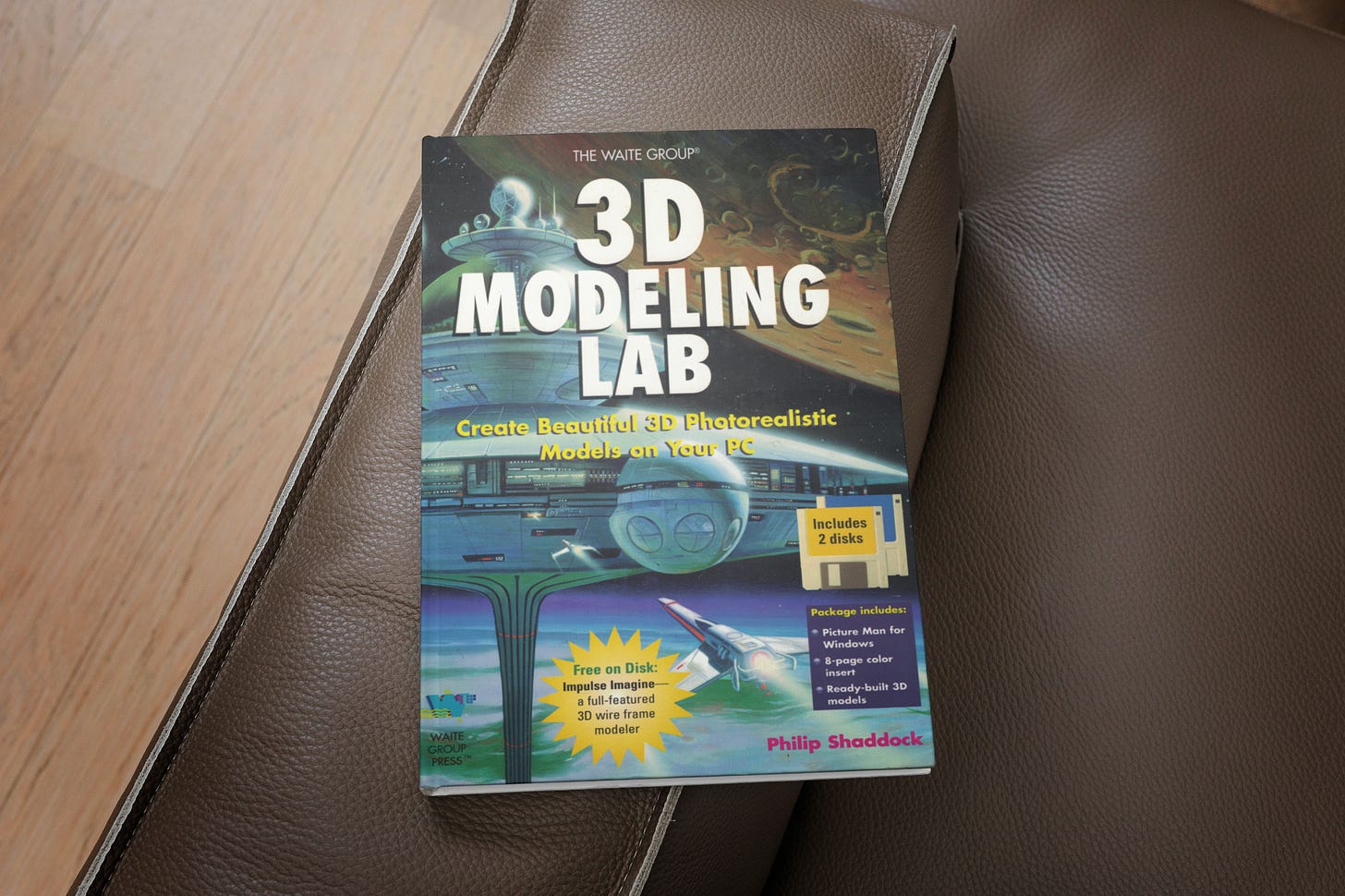

In 1994, I bought a book called 3D Modeling Lab, which was essentially an introductory course to learn the basics of 3D. The best thing about it was that it included a floppy disk that contained a copy of Imagine, which was an MS-DOS-based 3D modeling and animation package made by a company called Impulse that in many ways really changed my life. I pored over the book and immersed myself in learning Imagine. A few weeks in, I hit a road block. I don’t remember what it was now, but there was something that I couldn’t figure out. Since there was no Google or Reddit to just look it up, I did the next best thing: I called the company. Now that I think about it, I don’t even know how I found the number—maybe it was in the book. Regardless, I called them up. “Impulse, this is Mike,” said the voice on the other end of the phone. What I didn’t realize at the time was that Mike was Mike Halverson, the CEO of the company and he just happened to pick up the phone. We had a terrific conversation and he helped me figure out what I was trying to do in Imagine. A few weeks later, I hit another snag, called Impulse again, and Mike answered the phone again. Long story short, Mike and I ended up becoming friends and we even met up a few times at Siggraph, which is a conference for computer graphics and technology. Over the next several years, with Mike’s help, I continued to develop and refine my 3D skills and in 1997 was even part of a cover story in an issue of PC Graphics and Video magazine, which I think I still have somewhere.

I loved 3D. I loved that it became a natural extension of my sketchbook and I got to the point that I could model pretty much whatever I could sketch. To take something from a pencil sketch to a 3D model or scene that you could light, render, and orbit around or fly through was an incredible rush. I tried a bunch of different 3D applications besides Imagine, including 3D Studio, Softimage XSI, and Maya but I ultimately landed on an app called Lightwave, which has been used on a ton of movies and TV shows. I used Lightwave for years, both personally and professionally as an Art Director at Universal Studios. In 2002, Universal Studios was sold and our division—along with several others—was dissolved. I stayed on as a contractor with Universal Pictures, but by 2004 I was doing more straight ahead graphic design and basically stopped working in 3D altogether.

By this time, you might be wondering what any of this has to do with a watch. And the answer is nothing—not directly, anyway. When I saw Carl’s post about the watch, I went to his site where I spent more than an hour looking at his work, which is a combination of 3D models and animations, sketches, and UI designs. To say that it left me not just impressed but also inspired would be a bit of an understatement. It was a light bulb moment of the highest order. What do I mean by that? None of Carl’s objects—at least to my knowledge—actually exist. They all represent possibilities…the same kinds of possibilities that used to fill my sketchbooks. Maybe some are done as potential client projects, but I would bet that the vast majority are for his own amusement and enjoyment. I know this because until around 2004, I used to do the same thing. When I went freelance full-time, everything changed. In my mind, without a steady paycheck, everything I did had to point to getting the next gig, which meant that I had no more time for doodles and sketches just for fun. I was wrong, of course, but that’s the hustle mentality, right?

As I was looking over Carl’s work, I found myself coming back to the same question again and again. “Why don’t I do this anymore?” To be completely honest with you, I don’t know. As I said earlier, I loved 3D. I mean, when I stopped twenty years ago, it was because I was more concerned with finding the next gig. That’s no longer the case. Now, I am in an incredibly fortunate position in that I have an abundance of the one thing that most people simply don’t have enough of: time. I also have a variety of interests and a seemingly never-ending stream of ideas. So I asked myself, “What if I took some of that time and spent it trying to relearn some of the 3D skills that I used to have?” I’m sure a lot has changed in 20 years with regard to the software, but from everything that I’ve seen, the tools have only gotten better and more intuitive.

Carl uses an app called Blender for his 3D work, which I’ve known about and been at least loosely following for years. In fact, I first met Ton Roosendaal, who is the original creator of Blender at Siggraph in either 94 or 95 when he was first launching the software. Blender 1.0 was a vastly different piece of software than the current 3.5 version, which has grown from kind of a quirky niche piece of software (not unlike the early versions of Imagine) into a really incredible application that’s used in film, television, and game development by major studios and independent creators…and it’s still completely free. I’ve spent the better part of the week going through some of my old sketchbooks to see if there’s anything I’d like to revisit or whether I’ll just start fresh. I’ve also downloaded Blender and have been doing some of the introductory tutorials, which are going surprisingly well given how long it’s been since I’ve opened a 3D app. I don’t think it’s quite like riding a bike, but I think the odds of getting most of my 3D chops back are pretty good, especially seeing what the new software is capable of.

As you may have gathered, this week has been a big deal for me for a few reasons, not the least of which is that I can’t wait to see where getting back into 3D leads. But more than that, it’s been about getting to the point that I not only accept but am also willing to lean into the incredibly fortunate position I’m in and get back to making for the sake of making, without some ulterior monetary motive. I have a few projects that I’ve been reluctant to really commit to exploring because they may not end up going anywhere. But over the last few months, and especially over the past week or so, I’ve come around to the fact that an uncertain outcome, for lack of a better word, doesn’t mean that a project isn’t worth doing.

As I was finishing up this Iteration, I got an email notification—which I normally silence when I’m working—but for some reason I didn’t this time. The notification was from my friend David duChemin and the subject line read, “Having not gone farther.” Knowing what a brilliant writer David is and what he has recently been going through, I paused my own writing to read his. I won’t go into too much detail because I would love for you to read it for yourselves, but I would like to share two things from it that resonated with me, given what I’ve been thinking about lately. The first is a single sentence that simply reads, “We are made by the things we do, not the things we do not do.” The second is a paragraph that really hit home for me.

What I have regretted are the things I have not done. Conversations with the dying reveal this to be all too common: it’s not so much that we wish at the end of our lives to undo this or that, but to have another crack at what was left undone, untried. To say what was left unsaid, to have another chance at love that was never explored. To be the people that we knew ourselves to be, and could have been more fully, were we not so held back by fear. I think when we’re dying we probably see so much more clearly (and realized so heart-breakingly late) how truly trivial some of the things we feared really were.

Thanks so much for reading.

That's awesome! I got into architecture right before 3D became a requirement and never caught the 3D itch...I've dabbled in the world and it sure is powerful! Have you checked out the works of Ian Hubert, his Dyanmo series is awesome, as is his conversation with the Corridor Crew

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCbmxZRQk-X0p-TOxd6PEYJA

https://youtu.be/nN7rk3rj5mc?t=550