Discover more from Iterations

If you’ve spent any time around me at all, you know that I have opinions—lots of them—and I have since I was a kid. Sometimes when I would offer my unsolicited thoughts on various things, my mom would respond with “Oh, there he is…my little critic.” The thing is it’s not just criticism. Not always, anyway. More often than I generally care to admit, I find myself feeling personally offended, either by the design or functionality of a product or service or by someone—whether I know them or not—who simply doesn’t do something the way I think that it should be done. And to be clear, it’s not that I think that I’m better as much as I think that the way I do certain things is. I’m not right all the time and I have no problem admitting that. But when I am and I think that you’re not, I’ll happily tell you. I think it’s something I inherited from my dad—or maybe it’s a trait of undiagnosed neurodivergence. Either way, while I think I’ve gotten better about not being so critical (at least publicly), letting go of the behavior can be a mixed bag.

Because here’s the thing—on a fundamental level I actually think that criticism is an essential part of the creative process. Although as I hear myself say it out loud, that’s not quite right. It’s critique that’s essential, not criticism—and more than that, it’s invited critique. That’s where I (and maybe even you) often stumble. It doesn’t help that social media makes it extraordinarily easy to be an armchair critic—or expert, for that matter—on virtually anything and anyone. But even without it, for some of us, it’s just an easy mode to fall into.

I was talking about some of this with Sean the other day, who as many of you know is one of my closest friends and is someone for whom I have an immense amount of respect. He is incredibly empathetic, but more than that, he is willing and able to be the voice of accountability, which is something that I have learned that I need in my life. He is one of those friends who is not afraid to call me out or hold my feet to the fire, and because I know that whatever he says is coming from a place of love and respect, I can often hear things from him that I am unable or unwilling to hear from pretty much anyone else. If you don’t have someone like that in your life, I strongly recommend you make it a priority for the coming year. It is so easy to get stuck in our own patterns and in our own heads and having someone we can trust who exists both inside and outside of our orbit—and who is able to see things that we can’t—can be an essential resource (for lack of a better word) in helping us to get unstuck and to keep moving and growing.

So as Sean and I were talking, he asked whether I’d ever heard a Teddy Roosevelt speech called The Man in the Arena. I told him that I hadn’t and he said that he thought it might speak to some of what I have been feeling and trying to process. He asked if he could read it to me—and of course I said yes. Just as a side note, if Sean ever offers to read to you, I recommend that you take him up on it. If you’ve listened to the audiobook version of The Meaning in the Making, you know what I mean.

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

Hearing that set me back on my heels a bit. But rather than getting defensive and hearing it as some sort of indictment, I considered the messenger and instead heard it as an opportunity—a thoughtful invitation to look a little deeper at some of my own behavior. As we continued talking, he reminded me that by criticizing instead of making, we’re just trying to keep ourselves safe—from ridicule and from potential criticism of our own. That really struck a chord because while I’m not typically publicly critical, behind the scenes it’s definitely something I’ve been working on.

A couple years ago, Adrianne turned me on to Simon Sinek, who really gained popularity with a TED talk and a book he wrote called Start With Why. I know I’ve mentioned it before, but ever since I read the book, I think I’ve been on a path to asking a different and maybe a better kind of why—certainly of myself. To be clear, I am very curious and inquisitive by nature—and have been since I was a kid—but I think Simon’s book helped to inspire me to look for what a deeper, more personal why might look like, at least when it comes to my own work. There’s one quote from the book that has stuck with me, and if you’re a maker of any kind, it might apply to you too. “People don't buy what you do; they buy why you do it. And what you do simply proves what you believe.”

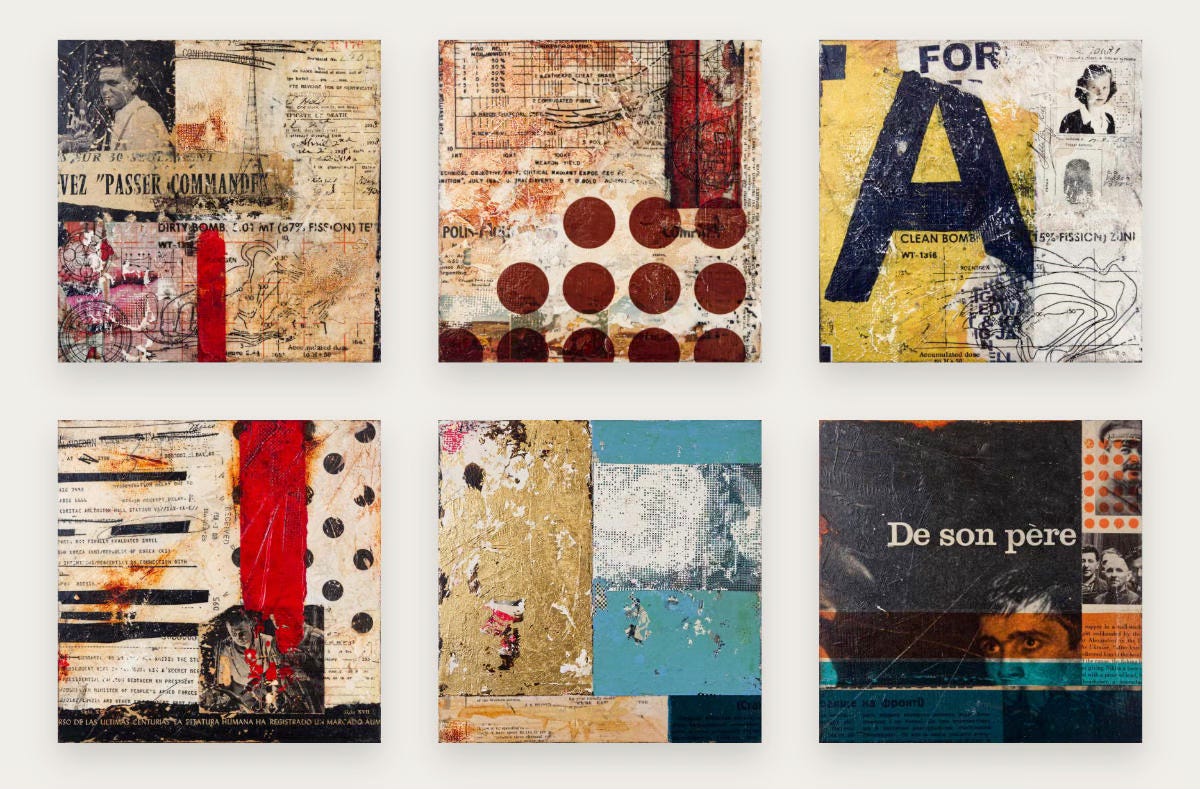

For me, that hits close to home because for the past couple of years—maybe even longer—I’ve really been trying to figure out why I do the things that I do in terms of my creative practice. I’ve talked at length about the various things I do, but rarely have I talked about why I do them and maybe more importantly why I don’t—mostly because I didn’t really know, or the reasons I kept telling myself felt inaccurate. Because of that, I haven’t been very productive over the past couple of years. As Adrianne pointed out recently, “You’ve been doing the work, but not necessarily producing the work.” There’s a big difference and she’s exactly right. Yes, I’ve made some paintings and I’ve recorded a few podcasts, but other than releasing weekly installments of Iterations, my output has been fairly poor—certainly not where I think it could be. I think one of the reasons is that I couldn’t articulate a why that made sense to me. I’m not chasing fame or followers or even money for that matter, so why do I make? I have several creative friends who have told me that they “can’t not” do what they do—that it feels more like a calling than a conscious choice. I’ve often found myself envious of them because I don’t really feel called to do anything, which I think at least partially explains why I don’t produce more than I do.

I think a recent “aha moment” came in the realization that my why is actually very simple and it’s pretty much the same as it has been for most of my life. I love the process of making. It’s really that simple. And it doesn’t matter what kind of process we’re talking about as long as there’s thought and effort and maybe, if I get lucky, some sort of transformation, personal or otherwise. I’ve said several times that when Adrianne sees me come upstairs from the studio and I’m covered in paint or I’m still buzzing from a conversation I’ve just had, she knows it’s been a good day. It’s when I pile on things like expectations around performance and reach or monetization or wondering what (if anything) my work will mean to an audience that I lose interest in doing any of it.

This might feel like a heavy way to start the year, but I think going deep is sometimes the best way to get ourselves in motion. I know that’s often true for me. This is something that I come back to again and again and it’s one of the things that has held me back from making for years. I want to be an active maker who can offer informed critique, not just a passive voice from the sidelines serving up empty criticism that does little, other than somehow allowing me to feel better about what I’m not doing. One of my hopes in talking about this is that it might help start a conversation, either between you and me or maybe between you and a friend or family member.

If it does resonate with you, and you’d like to talk about it, feel free to reply, leave a comment, or email me at talkback@jefferysaddoris.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Thanks for reading.

What a great post, Jeffery!

Totally resonated with me -- the importance of critique and finding people who can deliver it lovingly and honestly (very hard to find them), the Roosevelt speech, which I hadn't been familiar with, and the work of Sean Tucker, whose book I'm about to buy. Thank you.

You’re in my head again, Saddoris! Where you use the word criticism, I use the word judgmentalism. I’ve concluded that fearing others’ judgment feeds into my being judgmental of others. Or maybe it’s the other way round. I don’t really know; and it doesn’t really matter. It’s very tiring. As I create and publish what I do, it reveals the flaws of mine that bother me the most and that I wish to change. Being judgmental of others is high on my list, and I’m already beginning to experience a feeling of being able to publish my content less fearfully. It’s a nice feeling.